Preface

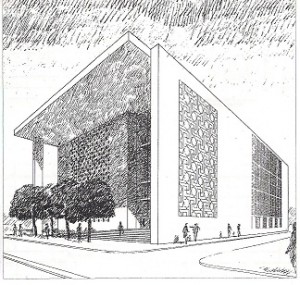

Situated opposite the Nativity Church of Bethlehem, the Peace Centre was built to celebrate the millennium, and was funded by the Swedish government.

“Without a doubt, the house of culture and the square in Bethlehem is one of the most remarkable Swedish architectural assignments ever”, wrote Johan Mårtelius, professor of history of architecture at The Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, commenting on the project in the magazine Architecture 1 in February 2001.

Christmas 2012 marks the twelfth anniversary of the project and, as its architect, I feel I have a responsibility to record my experiences and give my picture of this project.

In the first chapter, I have chosen to put the project into its context, how it started and also to give my picture of the country, the people and the city of Bethlehem, the Nativity Church with its fascinating history. Chapter II concerns the actual project. In the third chapter I describe the two assignments I had in Palestine after the conclusion of the Peace Centre. In addition there is an eye-witness account of the massacre in Bethlehem and the siege of the Nativity Church in the spring of 2002 which, in my opinion, have received inadequate coverage in Sweden and in the rest of the western world.

To complete the picture, I have included my impressions from journeys undertaken in the region while the work was progressing. I should emphasise that my work with the project radically changed and deepened not only my view of Israel and of the Palestinians’ situation, but of the world in general.

The success of this “remarkable” project is due to the work of many people. I remember especially Göran Tannerfelt, CEO of SIDA(Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency) who supported me unflinchingly and also Sten Lööf, SIDA’s project manager, who saw to it that the project’s funds were used correctly and that everything went according to plan and on time, even though we did not always see eye-to-eye on things.

I would also like to thank my friend Lasse Wilhelmson for his untiring encouragement, help and good advice that have made my story possible.

I have taken most of the pictures myself. Those marked ML are the copyright of Maria Lanz.

Gotland in the Summer of 2012

Snorre Lindquist

- How it all began

- Why Just Sweden?

- Israel and Palestine, reflections

- The City of Bethlehem

- The People of Bethlehem

- The Nativity Church and Manger Square

- A description of the house of culture and the new square

- Work in Bethlehem

- World champions in stone masonry, excellent smithworks and more travels

- An archaeological discovery and a burst water pipe that could have ruined the timing of the project and caused Sweden great embarrassment

- My extra assignment as the city’s pessimist

- The journey for a High Court in Gaza and one in Ramallah

- Israel’s army invades Bethlehem

- Reporting for Sweden’s Architects

- Epilogue

Chapter I

- How it all began

A beautiful morning in early summer of 1997 when I was on my way to work in the Old Town of Stockholm, I met my colleague Alexis Pontvik. He had assembled the programme that would launch a competition for architects, involving a square and a culture centre opposite Bethlehem’s Nativity Church. I knew about it. But my wife and I were going away on holiday in three weeks time so I had not even considered taking part.

“Aren’t you going to compete?” asked Alexis “It ought to be right up your street”. It suddenly occurred to me that I could take some time off and that I might enjoy the competition, a pleasant way to pass the time before our holiday started. So that’s what I did. Serious work as an architect involves a visit to the location before sketching begins. I am a little ashamed that I was not able to do this, but time was too short. Nyréns, the firm of architects I worked for, allowed me to use the workplace for my project for the competition.

The competition programme proved to be excellent. I found it contained most of the information I needed to get to know the subject properly. I became ever more involved the deeper I delved into the assignment. I was lucky to have my colleagues at hand – Erik Möller, Karim Mehdi (then Raileanu) and Per Axelsson were my sounding boards and advisers and their reactions gave me self-confidence and ideas. The office was almost empty because of the holidays so there I sat, far into the light summer nights for three weeks until, exhausted, I went away on holiday. Our kindly caretaker, Lars Wellsjö, promised to see to it that the proposal reached Bethlehem one and a half months in advance.

In September Alexis Pontvik rang from Bethlehem. The votes were in and a unanimous jury had awarded me first prize! Thus started this amazingly different and challenging architectural assignment; a job I would never have dared to dream about, by a twist of fate, had come my way.

Happy and full of anticipation I travelled to Bethlehem together with the other prize winners and the project managers. Alexis Pontvik was our knowledgeable guide. Anyone who was someone in the city seemed to have assembled in the town hall for the prize-giving ceremony. This project, to be fulfilled before the millennium, inspired great interest. The millennium celebrations would be a time when hundreds of millions focused on how Bethlehem was being restored, preparing to receive thousands of tourists and pilgrims. This meant jobs and income.

Patriarchs representing the four oldest Christian communities sat in front of the podium, peacefully lined up in their distinguished traditional black attire. I was told that this was an historic occasion. For hundreds of years, in fact since the beginning of AD 800, because of Charlemagne’s conflict with the Byzantine Empire, the Christian communities, especially Roman Catholics and Greek Orthodox Catholics, have been enemies and competitors for the ownership of The Nativity Church. They have fought in various underhand ways for every centimetre of floor space (among other things, these disputes are said to have led to the outbreak of the horrific Crimean War in 1853). Michael Nasser, related to the mayor Hanna Nasser, and manager of the project for Bethlehem, told me that he had at times negotiated in difficult situations. A dispute concerning ownership occurred once when a window in the nave fell down. He arranged for the city of Bethlehem to pay the cost of repairing the window.

On another occasion he was witness to two monks fighting each other viciously with brooms over the boundary for sweeping rights. If you do not believe me, you might like to view this video film of another incident: http://arabnyheter.info/sv/2011/12/30/rival-clergymen-fight-with-brooms-at-church-of-the-nativity/

After the awards the mayor took me out on to the balcony facing the square for a private talk. He pointed to the smallish house in the gardens, owned by the Greek Orthodox church and close to the entrance of the Nativity Church. It contained a posh restaurant and a bank. He hinted that this proximity to holiness was indecent. He himself belonged to the Roman Catholic church.

Off the record, the mayor ordered me to re-design the culture house so that its restaurant was closer to the Omar mosque on the other side of the square instead of to the Nativity Church, as I had drawn it. And, he went on, the six springs I had drawn on the square for visitors’ well-being had to go, they would be used by Muslims for ritual washing before Friday visits to the mosque; displeasing to Christians considering the proximity of the Nativity Church. Likewise the arabesque pattern on the stone floor of the square had to go as it would remind people that Islam had a presence here.

I suddenly felt I was walking on a mine field of religious contradictions, hidden from the rest of the world. I later realised that the mayor’s opinions were not those of ordinary people. The Muslims in particular showed restraint, they did not share the mayor’s attitudes. They have always had respect for the Nativity Church which they proudly consider theirs – as well.

I did not want to start off by appearing quarrelsome so I redrew the house. The result was more or less a mirrored version of the original plan with minor changes. The springs became cubes of stone with water trickling down them, the pattern became more discreet but still Arabic. I came to realise how easily the project could be toppled by collisions of strongly held opinions and decided from then on to stick to the award-winning entry’s chartered course.

Later on, when I had put together my team of Swedish architects, our thoughts turned to the lives of the people of the city. We saw hundreds of Muslims praying on Manger Square outside the Omar Mosque. We wanted to meet other people, some from Hamas for instance, not just Christians, and find out what they thought of our project. The mayor heard of our plans and intervened, forbidding us to make contact. Those hidden contradictions popped up again.

- Why Just Sweden?

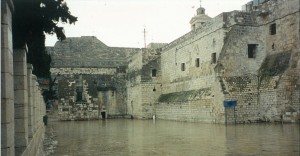

Around the millennium, many countries were involved in various aid projects aimed at getting Bethlehem back on its feet after 50 years of war and occupation. The sight of Manger Square put pilgrims and tourists off from going into the city to visit restaurants and shops. Alleys and squares looked shabby and worn. Manger Square, loud and untidy, was used as a parking lot for cars and tourist coaches.

Through SIDA (Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency), Sweden was committed to restoring some of the old town’s alleys , market places and Manger Square. The job of building a house of culture on the Square, situated where the British during their Mandate had built a large police station, came later. In collaboration with the City of Bethlehem, a decision was made to organise an architectural competition, open to Swedish and Palestinian architects. The competition included a redesigned square, some sort of temporary arrangement to hide the hated police station during the millennium ceremonies, and a proposal for a house of culture to be constructed a few years on. But when the competition was over, SIDA decided to fund and oversee construction of both a culture house and of Manger Square in order to have everything ready for the celebrations. The result of this decision was a huge lack of time in which to finish the project.

I was later to learn that Pierre Schori, former Swedish minister for co-operation and development was the driving force behind this initiative. When I started my job the newly appointed Swedish prime minister Göran Person had given the job to someone else. I never met Peirre Schori but my colleague Magdalena Franciskovic did, once at a construction site. Pierre Schori suggested the name Peace Centre for the culture house. Göran Person visited the building in connection with a goodwill journey to Israel and happened to speak to my Palestinian colleague Ramzi Kawar. “Looks like a box” was his sour comment. This was not his favourite project. His heart beat for Israel. At the inauguration he did not represent Sweden as we had expected, but chose to embark on a scandalous goodwill visit to South Africa with the purpose of selling a large number of Swedish fighter jets, hardly what the people there needed.

The Peace Centre and Manger Square project was a prestigious one, and many envious countries would have liked to get their hands on it. “Why Sweden?” was a question often asked by foreign journalists. The answer was that Sweden is known to the Palestinians as a capable and trustworthy country for managing aid projects. The project attracted more attention abroad that in Sweden. I was interviewed by a curious BBC, The Independent newspaper and other international media. Newsweek chose the restoration of Bethlehem as one of the twentieth century’s five most interesting building projects. But Swedish TV and radio never contacted us and Nathan Shachar of the broadsheet Dagens Nyheter waited until much later (see part 13).

However, Cordelia Edwardsson did interview me for Svenska Dagbladet, another daily broadsheet. She radiated sympathy and genuine commitment that warmed me instantly and made me more confident – under pressure, nervous and unaccustomed to all the shenanigans as I was. “The possibility of this vision succeeding without too much friction depends on a quiet, patient and tactful but stubborn Swede” she wrote. That was kind of her. But it was my colleague Erik Möller who was “quiet, patient and tactful”, I was the stubborn one.

The competition, open to Swedish and Palestinian architects, took place in 1997. The proposals were submitted anonymously. The jury consisted of a representative from SIDA, the architect Göran Tannerfelt, Alexis Pontvik, the mayor of Bethlehem Hanna Nasser, a representative from Palestine’s Engineer and Architect Association Nasri Morcos, architect from Bethlehem Georges Anastes, Jordanien architect Akram Abu-Hamdan and Spanish architect Professor J I Linazoro Rodrigues of international fame. Nyréns firm of architects, my employers, willingly helped me with the implementation of the project. They stuck by me even when I went beyond the frame of the budget, for which I am extremely grateful.

- Israel and Palestine, reflections

On our way to the award ceremony, as soon as we changed flights in the airport of Vienna, we were met by an armed Israeli soldier at the passport control. This was my first impression of the country. Not even the US, the world’s most powerful state, is allowed to stake out Europe’s passport controls with its military. In truth, the state of Israel is granted unique exceptions and favours I thought to myself. Indeed, what sort of country did we come to?

Historical Palestine is a narrow strip of inhabited land between the desert and the Mediterranean Sea that connects Africa and the flood land of Egypt with the northern continents and the flood land of Mesopotamia. Armies and migrations have washed over it since the time of the great flood cultures. Using this narrow strip of land, the human race spread out from its original area in Africa to Europe and Asia. Nowhere on our planet has there been so much bloodshed down through the ages. The proclamation of the Jewish state Israel and the Palestinians’ struggle for their rights is only the latest chapter of the story.

You would think that history had left its distinct mark on such a country, at least the last 500 years of history. When I travel through foreign countries, I like to look out for, and reflect on, the footprints of history. But the landscape that met us when we landed and were in a taxi on our way to Bethlehem was anonymous. It could have been anywhere in any industrial country.

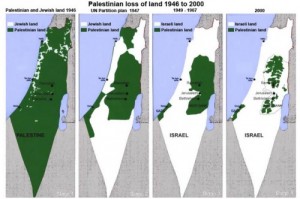

The history of the land seemed to have begun 65 years ago; something was missing: signs of the prehistory. There was however one special thing that stood out: the number of modern victory monuments along the road to Jerusalem. Spiked steel beams, abstractly fighting each other, a tank mounted on a roof, rusty old army vehicles that seemed to have been thrown out onto the side of the road. This latter monument was built on ground where the hardest battles were fought in 1947 when the country was “liberated”. The Palestinian village that stood here was pulled down and on its lands a landscape was created that would look naturally beautiful, as if it had always been there – Canada Park – for the newcomers’ leisure trips. Their leader Golda Meir said that immigrant Jews came to “a country without a people” – who was it then, one wonders, that they won their battles over? Any trace of the defeated has been swept away or hidden in the ground. More than 400 Palestinian villages and towns no longer exist. And the people who did not live in the country but must be defeated, where had they gone? To me, everything seemed artificial and sanitised by the victors.

Along the road up to Jerusalem, fertile plains gave way to dry mountainside and straight lines of young conifers. In the West Bank however, mountain olive groves are pulled out by the roots or burnt down. The best plants are sold to Jewish gardens. Olive trees are the Palestinians’ beloved national symbol.

Everyone spoke Hebrew. It is newly constructed as a spoken language and has been taught for a few decades. Some Jews were dressed as though they were living a hundred years ago; time was artificial too. We passed “The Green Line” in Jerusalem, the demarcation line set out in 1948 (see the map below the heading).All trace of it had been wiped out, but everyone knew where it had been and it is still significant. The occupied West Bank starts here and Israel enforces military law as though nothing had happened – eternally avoiding reality! There should have been a sign saying “This is Kafkaland”. Official language is like Orwell’s “New Speech”: war is peace, oppression is liberation, military violence is security, expulsion is migration and administrative internment is imprisonment without a trial. There was no barrier or wall separating the area when I was there, only these checkpoints, but we knew about them, or at least we thought we did (see part 5).

I tried to find a map that described in detail how military boundaries were drawn in connection with buildings, settlements, roads and topography, where checkpoints were situated, whether a road was a new road for settlers or meant for Palestinians and in which case, could it be reached by settlers. There were no such maps in the shops. Palestinian drivers knew anyway through bitter experience. Good maps of the West Bank are reserved for Israel’s military. The maps you could buy had Hebrew place names instead of the original Arabic names.

I hope I have here managed to convey the sense of confusion I experienced when I first came to this Disneyland, only for Jews, that is desperately trying to give the impression of a normal European country, but whose borders seem to float about, forever expanding, and straightforward questions are not welcome.

Israel and Zionism are secretive and inaccessible. There are strong forces in our world putting up smokescreens, spreading false rumours, raising obstacles that make understanding difficult. I am not saying that I know Israel in all its complexity. However, several ground breaking writers have served as eye-openers to me: Israel Shahak, Gilad Atzmon, Shlomo Sand, Ilan Pappe, Susan Nathan, David Hearst and Martin B. Qumsiyeh. There is a link on my website, “About Palestine”, where I have tried to give a short summary of the authors’ view of Israel. These facts are not very well known and they disperse the smokescreens. Their picture coincides with my impressions. I can recommend their books to anyone wishing to understand Israel.

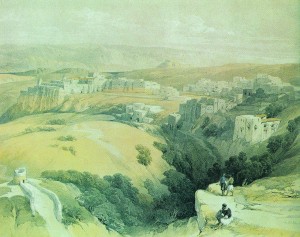

- The City of Bethlehem

Bethlehem is the most famous small town in the world. It has captured the imagination and fantasy of people for two thousand years. Even small children know about it. For Jews it is where their King David was born, the origin of the idea of a Messiah. For Muslims it is the town where Jesus was born, their greatest prophet after Mohammed. For Christians it is the town from where the message could be spread about Peace on Earth, a Saviour is Born.

Bethlehem is mentioned in ancient Egyptian texts and belongs, perhaps, on the list of the world’s first states, a stop on the trade route between the Sumerian and Egyptian flood kingdoms.

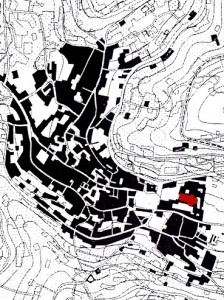

The oldest parts of the town lie on a winding ridge with deep valleys on either side, on the edge of the desert bordering the Dead Sea. In ancient times, the valleys were fertile. Rain comes in from the Mediterranean Sea during the winter months and is captured in the mountains. The water left over after replenishing the ground water is led by the deep streams of the valleys from the east side of the highlands out into the Judean desert, eventually evaporating before it meets the Dead Sea.

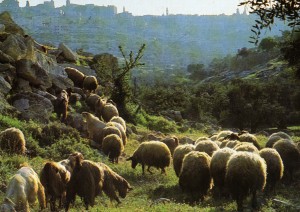

The top floor of the hotel where I stayed is Bethlehem’s highest point and I could see all round the horizon. To the north lies Jerusalem. It is a mere ten kilometres to the city’s old town, distances are short in this miniature country. In between lie Jewish settlements and, nowadays, the “separation barrier” that winds its way like a boa constrictor of barbed wire, electronic surveillance systems and parallel roads in the “shepherds fields”. These consist of a valley of green meadows and luscious terraces where almond trees bloom. It has now been torn apart and is in decay. Even apartheid South Africa fades in comparison with the racist contempt for others so visually demonstrated here, where both Palestinian and Christian values are destroyed.

I was able to follow the most recent settlement being built on Jibril Abu Ghnaim-height to the north west. It was confiscated by Jews and re-named, in Hebrew, Har Homa. Slowly but surely the hill was pulled apart by bulldozers, wiping out the ancient pilgrim route between Jerusalem and Bethlehem, while the world’s tourists and pilgrims passed by in coaches on the modern road, kept in the dark by guides who were always Israelis because all the coach companies are Israeli. Every month the woods, planted by people from Bethlehem and planned by the city for family outings, grew smaller. They have gone now and a proud, fortress-like town of stone sits high up on the hill, only for Jews. For pedagogic purposes, I created a special viewing terrace at the back of the Peace Centre where visitors could ponder this sight.

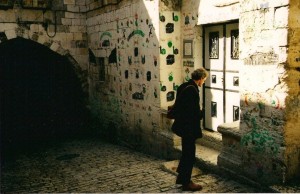

To the east, there was the old town centre with its winding alleys and conglomeration of old stone houses that originally consisted of cubes built together. Each cube indicates hall-like rooms that were added to others when needed. As the Peace Centre building progressed you saw these two tower-like daylight inlets rise out of the conglomeration.

In the background desert landscape, you saw King Herod’s original castle towering over the horizon, built like a volcanic cone with the palace at the bottom of the crater.

To the south and west, rolling mountain foothills are covered with olive groves with Palestinian villages in the valleys and Jewish settlements on the hill tops. A few tall pine trees still grow on the hills, the last remains of natural vegetation that has disappeared because of deforestation and decreasing ground water. Israel empties 90 percent of the West Bank’s water reserves for its own use or to re-sell at shameless prices to the Palestinians, the rightful owners, causing their farms to dry out.

Bethlehem and its satellite towns, Beit Jala to the west and Beit Sahour to the east, together with their surrounding countryside, are crowded with various charity buildings, cloisters and places of education that Christian communities have added down through the ages. The oldest cloisters are from AD 400 and have always been in use, others are isolated far out in the desert. Many mosques have appeared in later years.

The chimes of church bells give way to the muezzins’ loudspeakers that travel all the way to the stable where Jesus was born. The final hours of night echo with prayer and morning begins with barking choirs of dogs from housetops where they have spent the night.

- The People of Bethlehem

Christians have always lived in Bethlehem or thereabouts, even in times when Chrisitanity’s deeds angered Muslim rulers. Nowadays about 30 percent of the 40 000 inhabitants are Christians, and they are decreasing. At the beginning of the 20th century they were in the majority but then many emigrated to Southern and Central America. I was told that there are more families from Bethlehem in Chile than in Bethlehem itself. The hardship of living under Israeli occupation has caused many to give up and move away. Because of their mission, many Christians are well-educated and emigrating is not difficult for them. The arrival of refugees left destitute by Israeli occupation of their land, has increased the number of Muslims. They live in refugee camps that are 60 years old along the road from Jerusalem to Hebron. Palestinians share a common language, Arabic, and a common Arab culture which helps them to hold their own against threats from outside.

Those who have been forced to leave Bethlehem (and Palestine) still have the keys to their houses as a symbol of their origins and the dream of going back home. As a result, many houses in the city are empty.

Traditional life was characterised by six dominating clans, five of which were Christian. This is now changing with the times. The clans work as a social network in vertical lines from rich to poor. Many have been abroad to work or study. Because of Israel’s policy of expulsion and emigration, many have families and contacts abroad and they are good at languages, not just English. People are anxious to show their identity whether it is modern or conservative. The black Bethlehem dress with its beautiful embroidery on the front, is worn by many women, young and old, and many men wear Bedouin clothing.

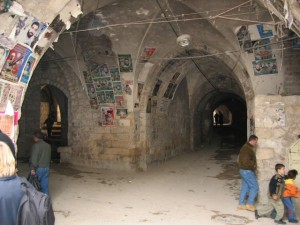

On market days, the alleys are full of visiting farmers and their donkeys. In the vicinity of the Nativity Church, pilgrims from all over the Christian world can be seen, fired with religious expectation, hoping to come close to holiness and dressed according to their respective beliefs and traditions. Few places in the world can showcase such a confusion of religious and cosmopolitan feeling, mixed with proud rural simplicity.

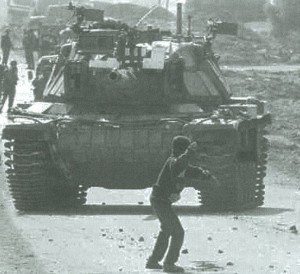

As a result of the first Intifada in 1987, Bethlehem is, on paper, an independent Palestinian city surrounded and controlled by Israeli troops. The systems of walls and barbed wire round the city is now said to be completed. The city is permanently under siege. Years pass by and Israel does not seem about to change the order of things. Nobody is allowed to leave the city except under humiliating circumstances with papers issued by Israeli authorities.

What I saw the first time I passed through the Israeli army’s checkpoint made me wonder. Large amounts of cars were parked in a disorderly manner along the side of the road and in the fields way out into the olive groves. People sat lined up on benches in control booths among the armed soldiers.

Why all this? I asked myself. I later saw the same sight every time I passed through. I now had an explanation. Unemployment drove desperate Palestinians to look for work among the Israelis, although this was forbidden by Israel several years ago.

Many squeezed into a car and drove to the checkpoint, parked where they could and sneaked on foot through the olive groves to the other side, where employers’ cars waited to drive them to badly underpaid jobs in Israel. It was all done fairly openly, I witnessed it myself. Once in a while the soldiers came to life and went on raids among the olive trees. Those who did not get away were arrested and placed on the benches pending transport to jail. There they were subjected to severe insults, interrogation and ill-treatment after which most were released. Women could usually expect to be sexually harassed. This was routine, I was told by many people, some who had themselves been victims. Those whose papers were not fully accepted were subject to the same treatment. It was obvious that there was a secret understanding between Israeli police and employers.

The Palestinians’ economy is almost entirely incorporated into that of the Jewish state. The currency is the Israeli schekel and they pay VAT to Israel. When it suits them, Israel denies the Palestinian Authority the refund that is laid down in The Oslo Agreement of 1993. Israel forbids Palestinians to export goods. Goods must first be sold to Israel and then exported as made in Israel. Nevertheless, Palestinian organisations support the current campaign to boycott Israel; the struggle for freedom comes first. Palestinians in exile make a significant contribution to the economy by helping their families at home financially. Aid flows in from the rest of the world – money to appease a guilty conscience and a substitute for real solidarity, which would entail forcefully defending the Palestinians’ rights.

Palestinians on occupied territory are thus dependent on aid which makes them automatically dependent politically on the donors and their ideas as to how the conflict can be resolved. This must be said, it is the truth, but does not diminish the importance of aid for the survival of the Palestinians.

Israel’s Jews are hoodwinked by their leaders and the media into thinking that the Palestinians are dangerous and cunning, thus the military, tanks, checkpoints, being tough and “separation barriers” are necessary. But all the Palestinians are asking is the right to run their country on their own terms and that their exiled refugees are allowed to come home and that their property is returned to them, as laid down in UN resolution nr 194. Alexis had told us to be prepared to see many Israelis openly armed on the streets of Jerusalem but that in Bethlehem the mood was less threatening. We found that he was right. There was a happy, friendly and peaceful feeling about Bethlehem.

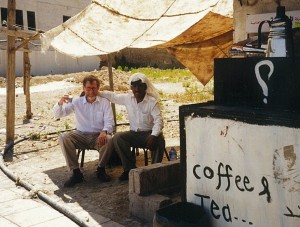

We spent an evening with Jamal Araj, our working partner’s boss, and he had also invited a Jewish landscape architect, Judy Green. They were old friends. It is very unusual these days for Jews to pay

friendly calls on Palestinians in the West Bank. But while I was there I did not once witness hatred of Jews or the Jewish religion. The people I met were very careful to distinguish between on the one hand Zionists whose ideology and goal is a Jewish state in Palestine at the expense of the Palestinians, and on the other hand Jews as people. There might be a different mentality these days, a result, no doubt, of the prolonged Israeli occupation and the heightened aggression of settlers and the army.

- The Nativity Church and Manger Square

I have found many of the facts for this part in Karen Armstrong’s excellent book “The Story of Jerusalem”.

Exactly when or where Jesus was born we do not know but it was probably right here – seven years before the beginning of our time – in one of the caves just outside the town used by shepherds and their cattle. Caves are still used to house cattle in these parts and there are many of them. Very soon after the death of Jesus the cave probably became the object of worship. But, as we know, Christianity was the enemy of the Roman state.

To stop pilgrims visiting the cave and to make people forget their faith, rulers under emperor Hadrian had a grove built over it, dedicated to the god Adonis. The sepulchre of Jesus in Jerusalem was given similar treatment. But apparently it had the opposite effect – the memory of the place stuck in people’s minds. In AD 200 the nativity cave is first mentioned in writing.

Christians, who were steadily growing in numbers, became a threat to the empire with their opposition to the religious status of the emperor as God. At the beginning of AD 300, the formerly so persecuted Christian faith was proclaimed by the emperor Constantine the Great the official religion, which proved to be a brilliant strategy. Thus the history of the western world turned over a new leaf. As a manifestation of the new era the emperor decided to build a number of monumental churches around his empire. This signalled the start of the history of architecture for western churches. The emperor focused especially on Golgotha, with the sepulchre of Jesus, and on the Nativity cave in Bethlehem. His devout mother, Helena, who had inspired his decision, travelled to Palestine to oversee the project.

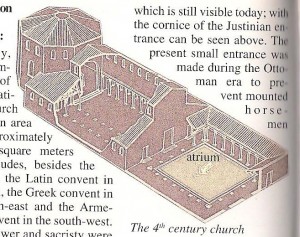

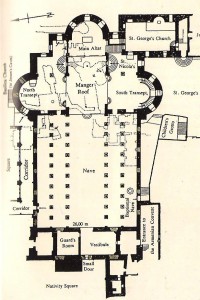

Earlier on, Christians had worshipped in modest locations, concealed in private houses. Building churches now immediately became an architectural task, aimed at shaping the ideas and beliefs of the people. The first nativity church in Bethlehem was built in AD 326. An octagonal temple was erected over the cave defined as the nativity cave, like a sanctuary, connecting it with a basilica-shaped meeting hall with five aisles. A courtyard surrounded by colonnades – an atrium – preceded this and the whole experience was one of degrees of holiness. (see picture in right column). It had the shape of a pilgrim church. The pilgrims could swarm in through the colonnades and aisles on one side and then, in rapture and prayer, wander around the entrance to the nativity cave, and then swarm out on the other side with no obstructions. Some hundreds of years later the church was destroyed during an uprising but some remains can still be seen, such as fragments of floor-mosaics in the basilica and details over the entrance.

In AD 529 a new church was built by emperor Justinian I, one of the history of architecture’s great builders, with masterpieces like Hagia Sofia in Constantinople and San Vitale in Ravenna to his name. The current space in front of the entrance is the size of the old courtyard which was pulled down. The basilica was re-built and instead of the octagonal room, three absides in the shape of a cross, with the middle of the cross covering the nativity cave, were constructed. (see picture in the right column). There is not much light and the interior is austere but nevertheless it conveys a sense of magnificence.

In the programme for my competition it says that the emperor Justinian was so displeased with the result in Bethlehem that he had the architect executed, not a common occurrence in the history of architecture I would think. To lighten-up my speech at the dinner held in connection with the inauguration of the culture centre, I mentioned Justinians’ execution of the architect and suggested it might be a way of dealing with me if the committee was not satisfied. Nobody laughed. An obvious culture clash – how could I think they would do such a thing?

The exterior of the Nativity Church is quite different. During its first few hundred years, the church was enclosed in a complex of dreary cloisters and now gives the impression of a patched fortress with unwelcoming stone walls. The entrance has been walled-up so that just a small hole remains and you have to bend double to get in. But Justinians’ church is still there, with all its vital parts intact despite the devastating earthquakes and wars the country has suffered for over 1500 years. This is due to a number of miraculous events. Awkward for Christianity, most events occurred thanks to non-Christian rulers actions.

At the beginning of the seventh century, the Persian king Chosroes’ armies ravaged the country and destroyed as many churches as possible, inspired by the country’s Jews, but they held back when they came to the Nativity Church. It contained a picture of the Three Wise Men, whose clothes they interpreted as being Persian, thus they were Persian kings. This was enough to spare the church.

In 637, the country was conquered by the magnanimous caliph Omar Ibn Al Kattab, who had been one of Mohammed’s most faithful followers. When Bethlehem was captured, he said his prayers in the part of the sanctuary facing Mecca. His reverence for Jesus was great and he made an agreement with the Christians, who he respected as “people of books”, that they had a right to the church which must not be destroyed, and that in future, Muslims should be allowed to pray in private on the same spot where he himself had prayed. This act would save the church the next time it was threatened.

In 1009, the demented and capricious Fatimid caliph al-Hakim was obsessed by the thought that Jerusalem’s church of the holy sepulchre was a danger to Muslims’ souls and ordered that it be pulled down, an order that, unfortunately, was obeyed zealously. Golgotha and the holy sepulchre were hacked into small pieces. However, the Nativity Church was spared a similar fate, thanks to caliph Omar’s decree. One night in 1021, the confused caliph rode out of his Cairo alone and was never heard of again, to the relief of all. Thus the fear that he would change his mind about the Nativity Church passed.

Bethlehem and Jerusalem were the great destinations for European pilgrimages during the time of the crusades. Hosts of devout tourists and adventurers filled the shelters and alleys, including people from northern countries. Indirect proof of this are the northern kings, Saint Olof and Saint Knut, who were honoured with their likenesses engraved on two columns in the church. The interior of the church was now given a thorough makeover and new rafters in the style of old ones were raised and lead tiles covered the roof.

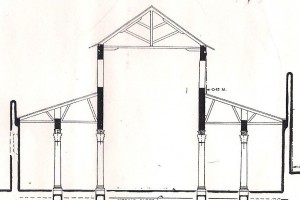

Controversy between the three rivalling denominations over the ownership of the Nativity Church, and obligations concerning its administration, has resulted in its gradual decline over many hundreds of years. During the time of their mandate between the two world wars, the British commenced an architectural investigation and undertook to restore the church. Since then, the dust has once again settled and there are new leaks in the roof. Maybe the walls of the side aisles have had openings for windows (like its sister church San Vitale in Ravenna), which were blocked when the cloisters were built. Anyhow this, together with the only inlet of light from the centre aisle’s upper part, with its bright modern plaster, creates an imbalance in the transmission of light into the interior of the church . This gives the somewhat gloomy and mediocre impression that visitors see today.

Just imagine if all the christian denominations in the world, in true ecumenical spirit, could end their feuds and agree on the administration and a thorough restoration of the church! To see the interior of the church clean from all dirt, new lighting and golden mosaics again covering all the walls and arches as they must once have been would give it a huge boost. Add to this the reinstatement of caliph Omars’s contract with the city’s Christians. These generous gestures would heal the wounds between Muslims and Christians created by the Jewish state and would benefit all, particularly the Palestinians.

In the 20th century when older buildings were pulled down, a new open space was created opposite the complex of the Nativity Church and cloisters. The place was named the Manger Square. Alongside the square and opposite the church, a 20th century Egyptian-style mosque was built to mark Islam’s presence and interest in the place. It has become too cramped for the growing number of Muslims and many say their Friday prayers on the square. Bethlehem’s town hall from the middle of the 20th century is close by, built in some sort of indeterminable desert style. The large police station built by the British during their mandate was also on the square. Even the Israelis used it when their army held the city, up until the time of the Oslo Agreement. Missed by no one, the police station was pulled down to make way for the Peace Centre.

Chapter II

- A description of the house of culture and the new square

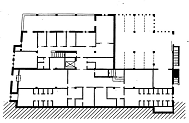

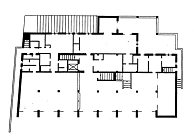

The culture house is planned after the fashion of Swedish “people’s houses”, e.g. for exhibitions, film-shows, talks, concerts, joint events and children’s activities. But also as an information centre for tourists and pilgrims, with service, toilets, bookshop, restaurant and garage. Rent from the latter would fund some activities. The house is open to all people of Bethlehem regardless of religion or politics, hence it is a welcome contribution in a country where organised culture events are usually connected to religious institutions.

The architecture of the Peace Centre is very unlike the architecture I grew up with which I found impossible to use in Bethlehem, especially for exteriors. The shape of the building is inspired mainly by Egyptian Hassan Fathy. This unconventional 20th century architect, almost forgotten these days, wanted to assert the values and potential of traditional architecture, as alternatives to technologically orientated modernism. He criticised modernism’s catastrophic blunders in the third world; he wanted to develop a way of building that was suited to poor rural populations, making use of their traditions and giving them a boost. Zwonimir Juric my colleague, now deceased, pointed me in the direction of Hassan Fathy and described Fathy’s imaginative way of creating a rythmic world of shape with moderate inlets of light and natural ventilation, in the traditional manner. There is a book about his ideas but very few actual buildings.

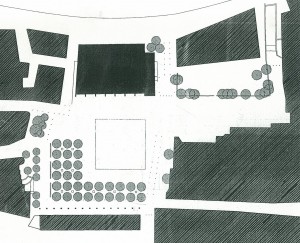

My vision was to create a calm, harmonious place that enhanced the ancient, venerable complex of church and cloister. I imagined making the square smaller to the eye, hiding the irritating 20th century buildings behind a screen of parallel lines of trees at angles. A stone pattern based on quadrants in the centre of the square would have a calming effect. Underneath the trees, springs with running water and shady park benches would be restful. No lamp posts, only shining globes hanging in the trees, similar to those in Stockholm’s Kungsträdgården in the fifties and sixties, and lastly, pinpoints of light in the stone pattern.. (Erik Glemme, colleague of the better known Holger Blom, came up with the idea of the shining globes). The beautiful marble inside the Nativity Church and covering the space outside can no longer be mined, the refugee camp Deheisha currently covers the deposits. Instead, I chose a lovely yellow ochre marble “Naqab”, mined in the Negev Desert and very similar.

My proposal for the competition included a pavilion with two floors that would create a visually calming wall for the square against the somewhat raucous façade of the recently built town hall. The pavilion would house a cafeteria where people could rest in the shade of mashrabiya (traditional perforated screens) in the openings of a wall, usually made of wood or gypsum with the perforations in intricate patterns) and still be able to see out onto the square. Some members of the city council opposed this. They said that the pavilion obscured the view of the square from the balcony of the city hall when they and their families wanted to watch the annual church processions.

The city council arranged a debate to which I was invited as the only listener from outside. It was a powerful show of Arabic eloquence which I shall not forget in a hurry. Since this event, I love listening to the beautiful Arabic language, although I do not understand a word. My friend, and Palestinian guardian, CDF boss Jamal Araj who was also a member of the city council, translated in elegant English for me. It was decided that the pavilion would be built according to plan. However, later on in the project the pavilion was cancelled due to funding reasons, and was replaced with some more lines of trees.

The trees chosen for the square are called Aish and are found in Palestine’s wild flora. Their foliage is dense, their branches graceful, they are resistant to drought and lose their leaves in winter. They are equipped with an irrigation system, just in case, to keep them thriving and beautiful. If it should fail we thought they would survive anyway. Landscape architects were Per Axelsson and Magdalena Fraciskovic.

Interior designer at Nyréns, Stefan Malmer, designed special benches for the square and they were made by a carpenter from Bethlehem. Stefan also planned the furniture of the house that consists of products from Åke Axelsson and Gärsnäs.

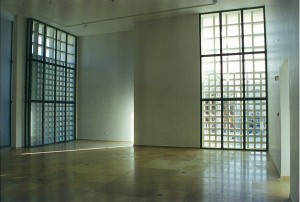

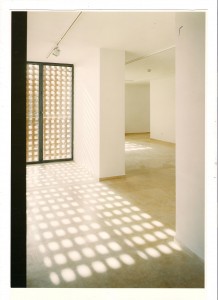

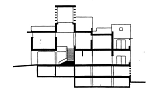

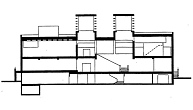

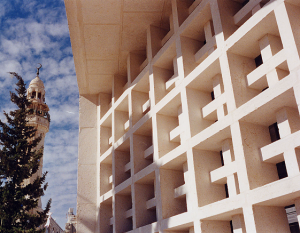

The broken forms of the culture house are inspired by the old city’s sensitive “cubic” building structure. The top floor façade, facing the square, is arranged in three parts, all with varying proportions and openings, but held together as one unit by arcades beneath, like an extension of the square into the house. These arcades facing the square can be opened up with large perforated steel doors to welcome visitors. From the cool shade of the arcades, the visitor walks towards the mild light, in the middle of the house. The light falls from the two tower-shaped inlets above the main stairway leading to the hall of light on the top floor, which spreads light to exhibition halls all around. They are arranged like an art gallery, where rooms with varying proportions and daylight inlets can be used with flexibility for different constellations.

To let light in through openings in the roof, a method common in art galleries, would cause problems here because of the heat of the sun at these latitudes. So I designed the façade with large

openings from floor to ceiling screened off by latticework outside the glass, inspired by Arabic screens (mashrabiya see above) in intricate patterns, only this time done in stone and simplified to patterns of squares. They give shade and allow soft light to filter into the rooms. The contrast of the smooth pale stone walls would set off the rough, crumbling stone walls of the church and cloisters.

The house’s signature – the two towers – work not only as screened windows to let in daylight but also as ventilation towers, in keeping with Arabic and Persian tradition. On burning hot days with no wind they work like chimneys. If it is windy, they catch the wind and fill the house with fresh air. The windows can be regulated manually on four sides. This is the way I gave the clients what they wanted – a method that is sustainable and largely independent of electricity and spare parts. Israel turns off the electricity as a way of punishing the Palestinians collectively.

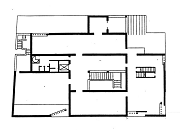

The back of the house facing the valley is terraced down a steep slope. This is the side you see first from the road. The supporting framework of the house is arranged in a grid that allows short spans, so load lintels could be avoided and costs spared. This has also given me freedom to choose room sizes, exterior volumes, roof levels and openings, and I have even managed to fit in a well-planned garage in the basement.

The Peace Centre is clad in Jamain, the white stone tinged with yellow ochre from Nablus, with a height shift of 50 cm. All the floors in the house are covered with Manger Square’s large-format Naqab stone with a finer-cut coating in the big halls and a smoth coating in the smaller rooms. All the inside walls are plastered and painted white. The inner doors and carpentry are of solid oak. I wanted the robust simplicity of old Bethlehem to be reflected in the Peace Centre.

A house of such quality as the Peace Centre, I thought, must undoubtedly have its own permanent art works by prominent Palestinian artists. At the Stockholm Academy of Arts, I saw a beautiful exhibition of Palestinian artists. I contacted the organiser Thomas Nyberg, but nothing ever came of it. Around this time, SIDA was starting to get cold feet, the financial framework of the project was coming apart and there was inside talk of Peace Centre becoming SIDA’s white elephant. I did not have the energy to pursue alternative financiers.

Part of my assignment was to work out how the forecourt of the Nativity Church could be illuminated by night. I arranged for light to drop down from each of the stone pillars that fenced off the adjacent garden, but more light was needed. I suggested hanging a large decorative lantern over the entrance to the Church which would cast strong light and shadow and effortlessly create magical focus on the sacred place. We had a 1/5-scale model in wood made in Sweden based on a sketch presented voluntarily by lighting expert Bengt Källgren. We liked his idea. We tried it out, hanging up a full scale dummy, but unfortunately the project came to nothing as we could not find anyone who could make the lantern. At the suggestion of Alexis Pontvik, the building was floodlit.

- Work in Bethlehem

My Swedish colleagues were the afore-named Erik Möller, Karim Raileanu and Per Axelson (the square) and later on Magdalena Fraciskovic (the square) and Stefan Malmer (furniture).

We had a daring and breakneck schedule considering all the unknown factors that could come to light: Israeli power cuts and closure of check-points, work and collaboration with a developing country we were unfamiliar with, culture clashes, our lack of knowledge of working in the country, difficulties of communication and what we considered completely unrealistic costing of 35 million SEK. We had only four months to complete the drawings and documents needed for contracting a builder. This was done in collaboration with a Bethlehem firm of architects and engineers that we had no previous experience of. These are extreme conditions for a project of this nature. In order to survive mentally under such pressure, I decided to divide my time into shifts of two to three weeks in Bethlehem and corresponding time at the office in Stockholm. It worked. In the peace and quiet of home, I could collect my thoughts, do my drawings and come up with solutions.

Erik Möller accompanied me to Bethlehem, kept an eye on the economy, calmly oiled the social wheels, if I might put it like that, and was also a confident architectural advisor.

Karim Raileau came too. His mother-tongue is Arabic and he taught me about the culture; he was also coordinator for computer design together with the Palestinian office. This turned out to be the issue that caused the biggest culture clash as I will show later on.

Per Axelsson’s research included which plants were available in the country and he completed the design of the square just how I wanted it. Without the intense, loyal support given by Erik, Karim and Per I would not have achieved very much.

The biggest surprise was our Palestinian partner, The Community Development Group (CDG), chosen by SIDA on my recommendation. Many Palestinian engineers and architects have studied in the west and returned home with good degrees. Hence, CDG was a very competent firm with, in many ways, a cosmopolitan image. But also a firm that had to battle with all the problems that occur in a country in the so-called Third World, suffering under the world’s longest occupation.

The Palestinians have learnt their fundamental building skills as underpaid guest workers in the Gulf states and in Israel. Unknown to most, however, it is mainly the oppressed Palestinians who have done all the hard work and, in actual fact, built most of Israel. Likewise the illegal settlements and the separation barrier. Beggars can’t be choosers as they say.

Israel’s deliberately unpredictable policies of punishments and harassment can create obstacles on the West Bank, such as customs trouble or power and water cuts or checkpoints. The Palestinians seem to have developed a work culture to cope with these circumstances. They make quick decisions, are ingenious at finding solutions and keen to be on time, they show a drive coupled with patience that is far from the picture I had previously had of Arabic work culture. Naturally they were also anxious to do their very best for this prestigious project. I am full of admiration for these Palestinians.

CDG’s work was based entirely on computers but they lacked any modern system, such as Computer Aided Design (CAD), one we were very used to working with at home. CAD makes cooperation very easy, both within the office and with other offices, and saves a lot of time. This was our culture clash. Karim had to intervene and hastily create a system for CDG, but there was no time for learning, we had to make do with make-shifts that complicated planning, caused anxiety and many surprises.

Four months was not long enough to develop all the details of the contract so when it later came to procurement and construction, I had to bombard our Palestinian partners with complementary sketches drawn by hand on A5 pages, faxed from Stockholm. I am too old to master CAD, a system that allows you to work from a distance using IT. A Swedish builder would have made a fuss over such procedures. But here it was accepted. My trips to Palestine were now less frequent, and I travelled alone.

A Palestinian architect from Amman in Jordan, Ramzi Kawar, helped me with matters of architecture. He was educated and had worked in the US and it was a great pleasure working with him. He could convey my wishes and questions perfectly to the office’s engineers. In the evenings we discussed politics and he gave me insight into the Palestinians’ situation.

CDG’s project manager, charming cosmopolitan and eloqent Jamal Araj, who had nurtured dreams of becoming an architect, arranged for us Swedes to visit workshops and industries to see what could be done with stone, forging, carpentry etc. Jamal invited us to his villa in Beit Jala. He had designed it himself and it lay on a slope. He had used this to create a magnificent high-ceilinged lounge with a view that stretched away towards Hebron. Deep down in the valley under the cliff, you could see the mouth of the car tunnel on the settlers’ good road from Jerusalem and southwards, only for Jews. At the other end of the tunnel the road runs over a bridge and disappears into a tunnel leading to Jerusalem, under the settlements on the hill Gilo that once belonged to the people of Bethlehem.

The settler roads run over bridges and into tunnels but the settlements on the West Bank are built on hilltops. The reason for this is found in Zionism’s surreal views, which were explained in the book and exhibition Territories by the architects Eyal Weizman and Rafi Segal. It goes something like this: the land “assigned” to the Palestinians as a favour is temporary, while the underground with its water, the hilltops with settlements and the airspace are “liberated” Jewish property. One day, according to this way of thinking, everything will be Jewish.

One lovely Sunday, Jamal took us by car to Jerusalem. He showed us his parents’ property that had been confiscated by Israel when they fled in 1948. Back in Bethlehem, he told us that our excursion had been undertaken without Israeli permission. If he had been stopped at the checkpoint without papers, he would have been jailed and subjected to the sort of treatment I have described in part 5. He had taken his brave chances against the persecutors. With us in the car, he could slide through. Being treated as racism’s favourites made us Swedes feel uncomfortable.

During the second Intifada in 2002 when Israel’s army invaded the three cities, Jamal’s house was shot at by machine guns. His children were alone at home and threw themselves down on the floor while bullets flew over their heads. One of his relatives had his house demolished by a missile. Jamal abandoned his home and moved with his family to his father in Beit Jahour. They now live in the United Arab Republic.

As a Swedish architect I had been trained to work at the early stages of a project with engineers and experts at calculating building constructions, heating and electrics etc. Their plans and the architect’s must be coordinated when they are handed over to the builders. Being a control freak, I usually took this upon myself. But there was a different routine here. Most architects hand their drawings over to the engineers who continue with theirs. The result can include unpleasant surprises in work where aesthetics are a priority.

This caused CDG a great deal of worry before they realised what I was trying to accomplish, and that I could be very stubborn, interfering and asked a lot of questions. Most of the time everything worked out well thanks to the flexible young team, that is, all except one: Haifa Hayek. A woman working as a constructor was uncommon in this technical world dominated by men, although women were starting to assert themselves more. But Haifa was respected and especially good at working out complicated calculations in her head. I could not communicate with her as her English was not good, and Hussam helped out. She sat silently in front of me with a little piece of notepaper, writing down something minute and nodding yes or no to my questions.

Sometimes she just left, without a word, and came back the next day, offering no explanation. No sketches of concepts were forthcoming despite my constant nagging. I was beside myself with anxiety. Eventually, after a few months, a thick package of drawings arrived. They did not show the contours of the bearing concrete construction with measurements as I had expected, but with the rebars inside, which was of no interest at all to me. However, everything worked when the house was finished so I need not have worried. I later learnt that she had five boys to look after at home. Perhaps she didn’t feel right about telling us this. All credit to Haifa Hayek.

- World champions in stone masonry, excellent smithworks and more travels

Early on I decided to use as few materials and products from Israel as possible, though I could not avoid them completely. Thus, stone masonry, forging and carpentry are all Palestinian. We did a lot of work looking into local opportunities. This meant many journeys along the West Bank and also in Jordan and Israel itself.

Stone for covering a façade is delivered as abraded slices from the stone industry and the surfaces are subsequently carved out by hand on location, on the side that will be visible, according to custom. This would be unthinkable in Sweden, the art of carving by hand is almost extinct and very expensive. The angled corner-stones were cut out of large blocks, using saws and mallets. A whole army of stonemasons were employed. Their ticking sound filled the house like music. The resulting stonework was a joy to see. There are no more masterly stonemasons than the Palestinians. All are intent on passing on knowledge and giving good advice to the architect. Stone masonry is, of course, the Palestinians’ national hand craft.

Strangely enough, the Palestinians have the British military governor from their mandate, colonel Ronald Storrs, to thank for the way things are today. After the Arab Uprising 1927 when the British took control of “the Holy Land”, Storrs was given the task of repairing war damage in Jerusalem. The administration of the sacred places was considered important. He also happened to be in love with Jerusalem and , in collaboration with the religious leaders and the city’s most prominent cultural figures, decided that all new houses must subsequently be built in domestic stone. The decision has been followed ever since and also applies to Bethlehem and other stone towns on the West Bank and in Israel. It gave rise to a stone masonry industry that has greatly favoured the Palestinians because they own most of the quarries and they own the traditional craftsmanship. Stone from the Holy Land is a sought-after commodity on the world market.

The stone for the façade was brought from Nablus where there are large quarries. To make sure that we were getting the right quality, we travelled to this awe-inspiring town that dates back to the beginning of urban construction. We chose an almost white, marble-like limestone called Jamaeen.

The historic part of Nablus lies wedged between two high cliff edges. On one cliff sits a Samaritan village whose inhabitants belong to an ancient religion that has something in common with Judaism, and on the other cliff is enthroned a Jewish army camp. Under the arches in the alleys of the town, the armed Palestinian resistance found protection from Israeli attacks. The core of the resistance on the Westbank is said to have been in Nablus.

A problem that gave me a lot of thought was how to make something that resembled a “mashrabiya” in stone; we had established that wood used outdoors had a tendency to crack and crumble in the local climate.

I searched for good ideas in every town I visited. In the end, I decided on an idea of my own. It might be possible to stack stones like a chequered grid. But how would it withstand wind and earthquakes? Jamal solved the problem. Stainless steel rods drilled into the stones,would keep them together. In Swedish tradition, logs are bound together in a similar way using dowels of hard wood. We experimented and it worked. I had been anxious, bordering on panic, that this idea would not work, so this was a weight off my mind.

In 2002, Sweden’s Stone Industry Union awarded The Peace Centre project the prestigious “Stone Prize”

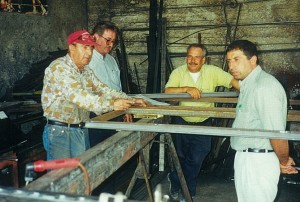

The large openings in the walls were another problem. Their stone grids naturally had to have inside floor-to-ceiling windows with double-glazing and insulation panels that can be cleaned from the inside. I hated the idea of using insulating glass attached to aluminium frames, partly because they were expensive to import and partly because they would look cheap anyway, and detract from the ideals of local simplicity that I had decided on. Erik, Karim and I went to Tel-Aviv – we were curious about the city but we also hoped to find a solution, which we did: Belgian-style slender, subtle steel profiles, first used at the beginning of the last century, joined together to make modern windows. It was difficult combining these Belgian-style profiles with the double insulation glazing. Nobody had ever even tried it before. But we solved this problem too, with the help of a Bethlehem blacksmith. He welded the huge story-high frames together with great precision, quite a feat.

We strolled around in the picturesque parts of Tel Aviv, built by the first Jewish pioneer settlers and now transformed into a very posh area. This is where I found the famous steel profiles. We went on to the centre of the city which is like an interpretation of the urban planning ideal Garden City and an architectural ideal of Bauhaus and Le Corbusier. An ideal city for modern socialist Jews , built largely by Palestinians without union rights on ground that was previously theirs. (Zionism is full of Orwell-like”Double Think”). In Hebrew, Tel Aviv means Spring Hills. The hills are the remains of Palestinian villages, so the town was built over these. Plaster-covered apartment tower blocks teetering on pillars were situated along leafy boulevards. Beneath the houses there was parking space and between them a communal park – this was the architect’s vision. But the ground floors have been boarded up and the so-called “white city’s” architecture is decaying, surrounded now by banks and hotels built in the usual skyscraper style.

An old school friend of Karim’s lived in one of these tower blocks and we were invited to her home for a meal. She had also invited a colleague from the firm of architects she worked for. He was a “Palestinian Jew”, e.g. a person who is descended from the tiny group of people with Jewish religion who have always lived in Palestine. Most of them come from the little community on the cliff south of Nablus’ old town mentioned earlier, and are used to living together with Muslims and Christian Palestinians as equals. You would think they would be revered by immigrating Jews as living examples that Jews have always been in Palestine. But no – their culture is Arabic, hence they are considered untrustworthy. They are looked down upon and subjected to discrimination.

Erik and Karim stayed the night at his friend’s flat. I chose to stay at a small hotel near the beach, a place said to be populated by all sorts of criminals. The hotel was good and nothing happened to me.

Next day, we visited the old port of Jaffa which nowadays is part of Tel Aviv. In ancient times, Jaffa was the first town where people on their way to Jerusalem usually stayed, when they reached the Holy Land by sea.

The ancient town of Jaffa was badly bombed by the Israeli army – Haganah – in March 1948. There were horrendous scenes of people throwing themselves into the sea in agonies of death, trying to avoid the bombing, and drowning, or squeezing themselves into the few boats available in an attempt to flee. Most of the town can now be seen as romantic seaside ruins of indeterminable origin .Visiting tourists and Israelis are not told about the history of the town and see nothing more than romance. We saw a bridal couple posing for a photograph in front of the ruins, with the sea as a background. Their car had a Palestinian flag. Was it defiance? Jewish artists and intellectuals have now moved into the picturesque buildings that have been restored, emptied of their original residents.

Our visit to Jaffa ended in the southern suburbs where the Palestinians who chose to remain in Jaffa live. There were nice old houses along the beach and on our way back we passed a lot of small Palestinian garages. Israeli cars are usually serviced by Palestinians.

Tired and hungry, we found a place to eat. It was full of Palestinian workers. As we were turning away somebody shouted to us in Arabic and “Saddam Hussein” was repeated several times emphatically. What were they telling us? Did they think we were Israelis and were taunting us with a tribute to Israel’s favourite enemy? Or were we seen as tourists who needed enlightening? Whatever the reason – Saddam Hussein was hugely popular with the Palestinians at that time, not without justification. The Palestinians do not love a brutal dictator, on the contrary they long for real democracy. But Saddam Hussein was de facto the only reliable support they had in the Arab world, and Palestinian refugees were well-treated in Iraq as opposed to the rest of the Arab world.

Later in Bethlehem, when I inspected the roof-work on the Peace Centre, I had a repeat of the event. In front of me, the Palestinian builders paid tribute to Saddam in Arabic. Perhaps they were curious as to how I would react. I waved jauntily and took a photo.

But back to my project. We had to draw the huge, heavy steel gates in minute detail in Stockholm in order to be certain that they would work and could be made locally. Project manager, Hussam Salsa, found a Palestinian blacksmith near Nazareth on the Israeli side, who would be able to cope with the complicated work. I went back again to check the result with Hussam Salsa, Michael Nasser and Ramzi Kawar, equipped with the Israeli authorities’ permission. The job was perfectly done. The fit was exactly right.

Palestinian towns are proud of their fine tradition of forging; front doors of steel decorated with ornamental metal work. We saw that pride of profession and craftsmanship lived on. A promise for the future.

In a taxi on the way to Jerusalem I saw something and took a photo: Israeli girl-soldiers, in happy anticipation, on their way to celebrate the jubilee of the “liberation” of Jerusalem in 1968. There is massive indoctrination in schools and the media in Israel, indeed the victor always tells the tale. It felt rather odd to sit beside a Palestinian taxi-driver and witness this scene – it was the subjugation of his own people and the military conquest of his home town that was being celebrated. What was he thinking while he watched this spectacle? I regret not having asked him.

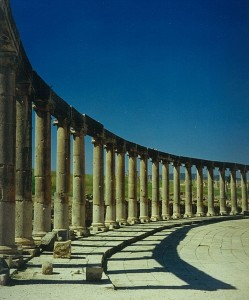

Once again Karim and I travelled to Amman where our Palestinian architect friend Ramzi Kawar worked and lived with his family. He wanted to show us Amman’s new monumental administrative centre, designed by Jordan’s most famous architect Akram Abu-Hamdan and exhibiting many interesting ways of treating natural stone. At the Jordan River Israeli border control, Karim was stopped and taken to a room for interrogation. His passport showed that he was born in Iraq and had been to Jordan before. Karim suspected that his Arab origins together with terrorist paranoia were behind it. Furthermore, Arabs in general consider that Jordan’s security collaboration with the Israelis is scandalous and, naturally, to Israel’s advantage. I became angry and phoned the Swedish embassy in Amman. I was told they had the day off. After hours of waiting and palaver we were eventually let through, greatly relieved. Whether it was because I phoned the embassy, or because they grew tired of us, I do not know. Just to make sure, a car with Jordanian military police followed us to our hotel in Amman where Ramzi was waiting. On the way back to Bethlehem we went north to see the impressive ruins of the Roman town Jerash with its ellipse-shaped forum, unique to the Romans.

One weekend, Erik, Karim and I took a day trip to the Dead Sea. We noted that we had never sunk so low (400 metres under the sea) while at the same time floated so high as in its cloudy chemical solution. We visited the remains of the town of Jericho with its surrounding walls, the oldest of its kind according to the information plaque, and the Masada fortification on the famous rock plateau with stunning views of the Jewish desert and the Dead Sea. This fort, shaped by nature, is Israel’s national monument.

One thousand Jewish extremists, a splinter group from the Zealots who rebelled against the Roman Empire, are said to have chosen collective suicide in AD 73 on the Masada cliff, rather than submit to the Roman armies – if you believe the Jewish-Roman writer, Josephus. The men killed their wives and children first before they themselves were killed by persons chosen by the group. When the Roman troops stormed the fortress they found all dead.(However, historians, even jewish ones, doubt that this is what happened). With this eerie legend as the silent subtext, Israel’s trained soldiers swear their oath of allegiance on the Masada cliff rock. Before the hundred-year epoch of Zionism, Masada was unknown to Jews, now the cliff is an Israeli symbol for its armed forces.

- An archaeological discovery and a burst water pipe that could have ruined the timing of the project and caused Sweden great embarrassment

While digging for the new house, on the slope forming the culture house’s foundation, masses of landfill were found, at least three stories high. It consisted of older houses that had been pulled down, probably from the time when Manger Square was built. It had to be removed and this meant building would be delayed. Right down in the bottom layers, remains of ancient houses and floor mosaics were found. An archaeological investigation found that they were from the Byzantine period. An aqueduct from Roman times that had supplied both Bethlehem and Jerusalem with water from Solomon’s dams to the south, has been discovered beneath what is now Manger Square. Hence it was supposed that the mosaics came from a Byzantine bath house.

We were told by the Palestinian Authority that the mosaics must on no account be removed from where they had been found, and that they should be made accessible to people when the house was finished. They were found right under the hoist way for the lift, of vital importance to the supporting structure. This threatened to cause panic in the project – our work was supposed to be finished for the millennium celebrations where the culture house had an important part to play. After working round the clock, I came up with a suggestion for an offloading construction which I faxed worriedly to Hussam from Stockholm. Happily he said OK and in just a few days the calculations and drawings for the construction were ready – thanks to our Haifa Hayek mentioned in part 8.

This was unequalled teamwork.

Nevertheless, not such a happy outcome of the damage to the main water pipe that ran beneath the road leading to the house. It sprang a leak caused by the building work, and the precious water undermined the ground and washed the road down hill. It was not discovered until the next morning and all traffic to the building site had to be stopped. This meant three months’ delay of the project. The pressure was on, more workers were employed and strangely enough, we caught up with our schedule and the Peace Centre was ready in December 1999 as planned. True proof of Palestinian efficiency and skill.

- My extra assignment as the city’s pessimist

With the approach of the millennium, people were growing nervous. Bethlehem’s city council was under pressure from people and organisations all over the world with some very odd ideas for projects, often mixed with barely disguised self-interest and suitcases full of money. The council needed an outsider who could say no, in a diplomatic but unwavering manner, to avoid becoming involved in lengthy harassments by insistent persons who they did not want to offend. This delicate task fell on me.

When Michael Nasser, with a little Mephistopheles smile, asked if I would do it, he said I could always say that their ideas conflicted with the big project opposite the Nativity Church. I didn’t want to appear difficult, and so it came about that I was installed as an authority, with visiting hours announced in advance, in a room adjacent to the hotel lobby, in order to meet with these people and their proposals.

There was an elegant man with a Ph.D., sent from the city of Verona and a religious culture organisation with connections at the Vatican. The project consisted of a huge arc of stainless steel that would soar over the culture house and land on the Manger Square. It was meant to symbolise Christianity link with the place, particularly Roman Catholic Christianity one understood.

The Anglicans in the US were represented by an American architect. The idea was that the Anglican church would take over the project and the architect would re-design it into a magnificent exhibition of the nature of Christianity (Anglican of course). I was invited to join in and have my say. Such insolence.

Russia sent a small delegation but with the most imaginative idea. A large, gold-plated star-shaped sculpture with built-in transmission installations is placed on the square. Out in space, a bright shining star would float above the Nativity Church, like the new star of Bethlehem, from which the celebrations can be transmitted worldwide, with breaks for commercials and the Christian message. Commercialised space-cooperation would be established with the US, everything was prepared and the money was there.

There has always been much speculation about what might be found in the bottom layers of Manger Square, but no real excavating has ever been done. With the new archaeological discovery of the Byzantine mosaics beneath the old police office, the people of Bethlehem wanted to know more. A delegation of local moneyed merchants was sent to see me. They wanted to stop the building-work on the square. A sizeable archaeological excavation was to be funded. Who could know what sensations would be uncovered? The findings would be exhibited to pilgrims and tourists who could also take the opportunity to buy religious souvenirs and presents in the hall. On top would be Manger Square. And how did the acting person of authority react? The answer was short and straight: no, no, and no again!

Chapter III

- The journey for a High Court in Gaza and one in Ramallah

With the project completed, I had travelled to Palestine eleven times. I described in a magazine the mood of the people of Bethlehem, as I understood it during that time, thus:

“The relief of being free from foreign soldiers, if only for a short time on an artificial island, sang in the air. Money from aid countries and exiled Palestinians’ investments kept coming, but to no avail: the Palestinian economy became progressively worse due to Israel’s trade barriers and checkpoints, while Israel’s economy blossomed.”.

But this was the best time for me. The Wall had not yet been put up. That would take two more trips.

However, six months into the twenty-first century, bad times were ahead. The second Intifada, triggered off by Ariel Sharon’s unprovoked decision to allow thousands of Israeli police to insult Muslims’ third most holy place in the world, Haram al-Sherif in Jerusalem. The Palestinians rebelled and their economy sank like a stone.

In Autumn 2001, Hussam Salsa phoned me, he desperately needed assignments for CDG, otherwise he would be forced to let people go. He wanted me to work with CDG on a competition proposal for the coming Palestinian state´s construction of two large buildings for the High Court. One was to be in Ramallah on the West Bank, the other in Gaza.

The local programmes were identical for both. The World Bank stood as guarantor and Saudi Arabia was the financier. The very fact that there were to be double authorities for the coming state, because Israel controls the links between the two parts, made it obvious how far from reality a two-state solution was, and still is. With the US controlled World Bank running the show and the Saudis as consultants in ideology – their first condition was that both buildings should have a built-in mosque – you could predict the outcome would be court buildings for a resigned, corrupt and fragmented Bantustan. Virginia Tilley writes about these problems in the article “Bantustans and the unilateral declaration of statehood”, November 19th 2009.

http://electronicintifada.net/content/bantustans-and-unilateral-declaration-statehood/8543.

Hussam beseeched me and I felt I couldn’t let him down. Nyrén’s architect firm suggested Ahrbom Partners, a firm of architects that specialises in court buildings.

In November – December 2001, I went to Ramallah to give an account of our ideas to the competition jury. I was thoroughly short-changed by the Palestinian taxi-driver. These were different times, the Palestinian leaders’ corruption had spread to the people.

Driving to Bethlehem in Hussam’s car we found the checkpoint at Kalandia closed by the fickle Israelis. So Hussam drove routinely right out into the open fields until we reached another road and eventually Bethlehem. Closing checkpoints is usually quite random and meant to bully people, it normally has nothing to do with Israel’s security. If the one we had just encountered had been serious, we could easily have been stopped by Israeli soldiers. The real reason is evidently different. Partly to convince ordinary Israelis that the Palestinians are dangerous and partly to make life difficult for the Palestinians and intimidate them.

A French architect, friend of the famous Jean Nouvel, won the competition. His proposal was elegant but, typically for the French, required technology that was far too advanced. I was relieved that I did not have to take part in something I didn’t agree with.

- Israel’s army invades Bethlehem

The daily broadsheet Dagens Nyheter had not been in touch with the project at all, but contacted us just before the inauguration. Now they were suddenly in a hurry. The journalist and leftist zionist Nathan Shachar was calling: “Could you write down a few words about your feelings for your work? Then call me back and read it out?” That was the whole interview. If I hadn’t been so taken by surprise, I could have said “Sorry, bad time, but I can ask my secretary to think of something”. Instead, I wrote this: